Warsaw’s Flirtation with Social Realism

When the photographer Karol Szczeciński took his seminal aerial pictures of the obliterated ghetto district in central Warsaw in 1945, the city’s population, eking out an existence in a city of rubble, numbered barely more than a thousand. Six years earlier the official count had stood at nearly 1.3 million and the determination to rebuild a city that their foe had sought to remove from the map, would bring with it the Herculean task of providing homes for returnees and new residents which, ultimately, would see the population return to its pre-war levels in a mere 20 years.

Szczeciński made a second flight some eighteen years later, to commemorate the anniversary of the liberation of the city from its Nazi occupiers. The pictures he took captured a city transformed and reinvigorated, the northern area of the ghetto now largely rebuilt with the extensive residential districts of Mirów and Muranów and the church of St Augustinian, preserved as a repository for stolen booty and captured in the earlier pictures as a lone survivor in the rubble, now surrounded by a dense pattern of residential blocks.

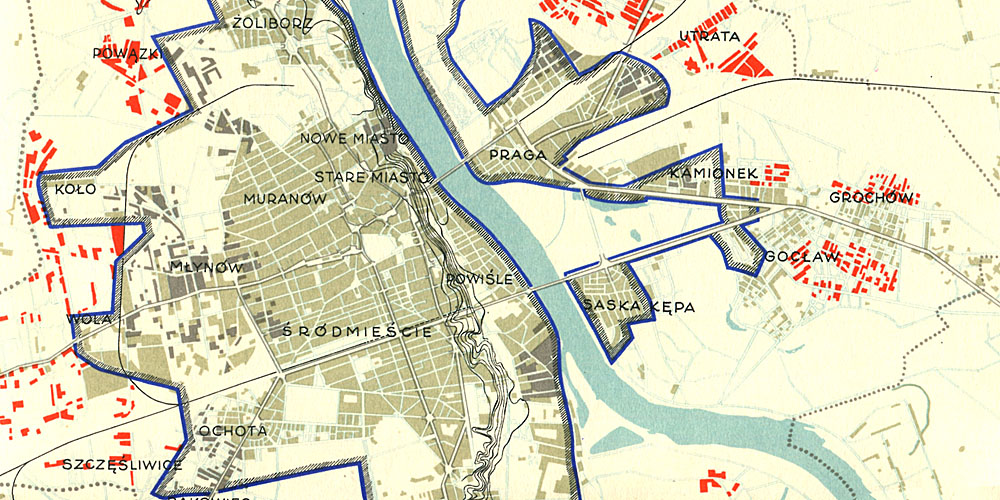

However, the city was not as densely populated as it had been before the war. Relative to its population, Warsaw covered the small geographic area of 118 square kilometres in 1939, giving it an overall density of 11,000 people per square kilometre (compared to 7,600 per square kilometre today in Śródmieście, the most densely populated district). With a gradual expansion of the city’s footprint and the replacement of former slum districts with what was perceived to be brighter, cleaner housing stock, the ambition was to create a social (and socialist) ideal.

Warsaw had flirted more than many European capitals with Modernism in the inter-war period, but the prominence of Corbusian followers in the post-war administration, including Roman Piotrowski as the head of the Capital Rebuilding Office, heavily influenced the strategy for addressing the challenge of mass housing. The opportunity that devastation provided was an almost blank canvas from which to create a modern city on the truly socialist lines set out by Le Corbusier in the 1920s. Architecture had been defined as a key front in the creation of a new social order by the National Council of Party Architects in 1949, taking up the clarion call of the CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) 1933 Athens Charter, which set out many of the socialist principles adopted in the command economies of post-war Europe and Asia. The Charter concluded:

“Private interests should be subordinated to the interests of the community.”

No greater call to arms could have united the architects and planners of this opportunity with the political will of the communist authorities. The professional class was leading the world in fulfilling the manifesto set out by CIAM (drafted, with no small irony, not in Moscow as planned but on a ship sailing to Greece, because Le Corbusier’s proposed design for the Palace of the Soviets had just been very publicly rejected by Stalin). Most of the political leaders held architecture in high esteem and saw it as a way of creating a physical permanence for their political persuasion. Some could even read drawings and their supreme leader, Bolesław Bierut, went as far as to sponsor a Six Year Plan, which envisioned a flourishing paradigm of socialist planning for Warsaw.

Whilst some of the mass housing schemes either planned or started before the war, such as the Brukalscy’s Ośiedle Żoliborz WSM, were completed in the immediate post-war period, none delivered anything more than a hundred new homes at a time. The planning of Ośiedle Żoliborz WSM was ambitious for the inter-war period, but not the direction needed to provide new homes for the capital.

In its introduction, Bierut’s plan claimed:

“The 6-year plan for Warsaw’s construction and development is part of a nationwide program of economic, cultural and social-economic reconstruction of Poland. The main task, the direction of this program is to create new, better and more rational living conditions for working people.”

In reality, it was the first, modern, comprehensive planning that Warsaw had benefitted from. It integrated residential provision with public space, cultural and political facilities and an all-embracing public transport system complete with a metro system. The introduction further set out the breadth of its vision and the part that the physical city was to take in the socialist ideal:

“New Warsaw is to become the capital of the socialist state. The struggle for the ideological face of our city must be carried out with all consciousness and all efforts in this direction. “

The plan did not, of course, envisage the dominant (nay overbearing) position of the Palace of Culture & Science, which appeared as a gift after its publication, nor the later brutalist monuments to public affairs, such as the Central Railway Station and the incipient move toward high rise buildings with the Intraco and Blue towers.

Whereas Le Corbusier may have been tempted to question the architectural purity of Social Realism in its adoption of a melange of Renaissance and Modernism, compromised by the limited supply of materials and skilled labour, at its core was a determination to create a city which was significantly better for its residents than the one before. Behind Plac Trzech Krzyży (and overlooked by the Party Headquarters) was to be a sports stadium of Grecian proportions. Public space was defined graphically and in seductive detail. The city was to work towards the benefit of The People.

Unexpectedly, the overall masterplan showed a degree of respect for the historical plan of the city and despite the ravages of time, the limitations of budget, the changes in political will and the yawning gap between dream and reality (a multi-line metro system was envisaged for the city by the mid-50s), a remarkable number of the key public spaces were created and completed with a high degree of faith to the original vision – Muranów, Plac Zbawiciela, Plac Konstitucji, and the wider MDM district, designed by Józef Sigalin. Even the social engineering in the artificial enhancement of the capital’s population evolved numerically pretty much to plan.

The confiscation of privately-owned land, facilitated by the Bierut-Dekrete of 26th October 1945, provided the vehicle for the core ambition of an unprecedented public housing programme. In the space of ten years, more than 60,000 people were housed in new flats in the Muranów and MDM schemes alone. The reconstitution of the framework, flesh and substance of society was funded publicly and, by default, privately by the un-volunteered donation of real estate. Notwithstanding the empty promise of compensation for claims made within six months of the decree being issued, without this public appropriation of the land upon which to build the new city, the scale and speed of the Warsaw’s recovery from its near total annihilation, may not have been as monumental if left to the original owners and other speculators in a period of such extreme austerity as the decade following the Second World War. The achievement is, of course, mitigated by the oft-repeated claim that only 30 of the first 150 flat delivered in MDM went to workers; the rest were given to party officials.

Ironically, in view of the political fanaticism of the first ten years of the post-war period, this was something of a golden era for the planning of the new city. The Plan itself is sometimes dismissed as a political nicety or a token gesture towards a city over which Moscow cast a long and dark shadow, but the reality is that a daring and holistic plan for the evolution of Warsaw was formulated, acted upon and, in no small part, delivered. With the demise of the ambitions of Social Realism and the withdrawal of its sponsors, the ability to coordinate a city-wide plan evaded subsequent administrations and the comprehensive planning and construction of the Six Year Plan has yet to be repeated.

The legacy of Bierut is perceived to be two-fold. The ferocity and vindictiveness of his political reprisals cost Poland some of its finest people, of the type who might have posed both a risk to Bierut and his regime and a resource for a different political direction. The second legacy is the lingering fallout of the 1945 decree and the continuing uncertainty about the legitimacy of land ownership.(10) Both of which inevitably obscure a remarkable vision – irrespective of political preference – for the recreation of a strong and vibrant national capital.

One long and fruitful outcome of the experience of re-planning Warsaw and other severely damaged cities, was the demand for Polish urban planners abroad, where long and robust reputations were established for the masterplanning of cities in Iraq, Algeria, Egypt, Syria and Libya. By the mid-1980s, Miastoprojekt alone maintained as many as 12,000 Poles in Iraq, upholding the manifesto of CIAM and establishing principles for urban planning still followed to this day.

By the time that Szczecinski took his commemorative flight in 1964, the high-ceilinged and principled generosity of Social Realism had given way to the pressing needs of cheap housing on a severely challenged budget. It died as an ideal along with Bolesław Bierut and his political sponsor, Joseph Stalin. As Szczecinski photographed a city reborn, the sprawling central Warsaw housing scheme of Za Żelazną Bramą was already being planned, cutting through the north central heart of the city to provide homes in four standard formats (27sqm, 39sqm, 48sqm & 57sqm) for more than ten thousand people and with little sympathy for the strategic plan or city fabric it cut through. It may have been faithful to Le Corbusier’s principles for high density living, but the physical manifestation turned out to be an open wound cut across the city, with little regard to the common space between which had previously been of such primary importance.

The residential estate had indeed become little more than a Machine for Living.

The fruits of Social Realism – the wedding cake architecture of a disingenuous period of political idealism tainted by atavistic selfishness – are now highly prized and much appreciated, both by the architectural community and by design-conscious home owners. The fact that they are increasingly owned by the resources that Bierut so despised is a fitting tribute to the legacy of an architectural fad and social experiment.

Paul Ayre

Warsaw, 27th March 2017

References:

- Przemysław Semczuk, “Karol Szczeciński, kronikarz PRL” Newssweek 4th January 2011

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Warszawa (web)

- Thomas Brinkhoff, citypopulation.de (web)

- Exhibition “The architectural legacy of socialist realism in Berlin and Warsaw”, Berlin, 24th August – 9th September 2011

- CIAM Athens Charter 1933, Getty Conservation Institute

- Martyna Obarska, Narodowy Centrum Kultury, nck.pl, 15th November 2011

- Bolesław Bierut, “Sześcioletni plan odbudowy Warszawy”, 1951

- Dziennik Ustaw Nr 50, 26.10.1945r, Poz 279

- Martin Sandbu, “How political revolutions shaped Warsaw’s postwar architecture”, Financial Times, 6th February 2015

- Grzegorz Wożniak, “70th Anniversary of the so-called Bierut Decree”, 28th October 2015

- Łukasz Stanek, “Miastoprojekt Goes Abroad”, The Journal of Architecture, 14th June 2012